Over and over again, I hear this from my clients: “I have been to physical therapy, tried yoga and Pilates, seen a chiropractor and had massages, but by far the best results I’ve found have been from working with you.”

Why do I get results for people suffering with back pain, stiff necks, tense shoulders, sciatica, scoliosis, and a bunch of other uncomfortable conditions when other methods fall short?

While I’d love to tell you I’ve got some sort of exclusive magic, the truth is it’s a lot simpler than that. The reason this work works is because I focus on the nervous system.

The Neural Factor

You see, muscles aren’t just meaty rubber bands that randomly get tight for no reason. Your muscles are controlled by a sophisticated software system — your brain. It’s nerve signals that tell muscles to contract or relax.

The problem is that accidents, injuries and chronic stress all contribute to muscle tension, and over time tension becomes the habit — your default neural set point.

Ever heard the saying “everywhere you go, there you are?”

Well, everything you do, there’s your neural pattern. So when you plant your hands in down dog or crank out a Pilates 100, you’re activating your unique neural pathways — almost like a personal movement signature.

That’s why traditional approaches often make good changes initially but sort of plateau at some point along the line. You get stuck in your own neural patterning. In order to break through this plateau and restore flexibility, you have to create new neural pathways.

A Different Approach to Improving Mobility

Fortunately, it’s a lot easier than it sounds. While this is the basis of the work that I do one on one with clients, there are also exercises that you can do on your own at home.

They’re easy, require virtually no equipment, and you can start to see changes in five to ten minutes (that’s about the same length of time it would take to watch two adorable cat videos on Facebook, for reference).

This is why I created Posture Rehab, a video suite designed to dissolve tension in your body and hit the reset button on your brain. That way, you can stand taller and move freely without tension, aches and pains.

Sound good to you? Click here for everything you need to know about the program — what’s included, a complete table of contents, FAQ, etc.

Posture Rehab isn’t yoga or Pilates — and it’s not designed to replace these practices either, but rather support them so you get more benefit out of doing them.

The Bottom Line

Listen, daily pain that saps your energy, degrades your focus, makes you cringe when your kid jumps into your arms, and wakes you up at night does not have to be your reality — no matter what your age. You can feel good in your body.

In fact, you have the right to feel amazing. Life is ridiculously short. Don’t spend your precious days in a fog of pain, limited by what your body can — and can’t — do.

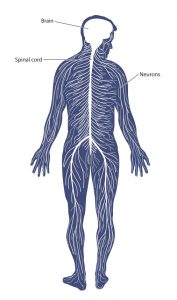

The gray matter of your brain condenses down to a ropy cord of neural material that runs through the core of your spine, branching out along the way into millions of nerves that terminate in muscles, bones, and organs.

The gray matter of your brain condenses down to a ropy cord of neural material that runs through the core of your spine, branching out along the way into millions of nerves that terminate in muscles, bones, and organs.

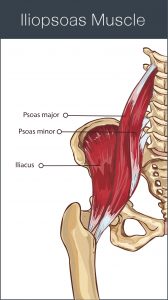

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.