I have never quite understood why psychology and physical medicine are separate branches of healthcare. It’s not as though the brain were a separate entity floating out there in the ether, merely tethered to a lumpy, unintelligent body like some supercomputer chained irrevocably to a vehicle that carts it around.

No, in fact, your brain and body aren’t distinct. They’re the same freaking thing. Your brain is your body, and your body is your brain. That’s basic anatomy.

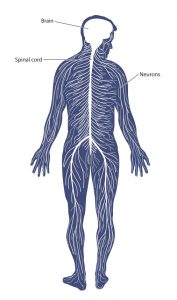

The gray matter of your brain condenses down to a ropy cord of neural material that runs through the core of your spine, branching out along the way into millions of nerves that terminate in muscles, bones, and organs.

The gray matter of your brain condenses down to a ropy cord of neural material that runs through the core of your spine, branching out along the way into millions of nerves that terminate in muscles, bones, and organs.

It is impossible to have a thought or feeling without a corresponding physical reaction. Impossible.

When you have an experience — any experience — every cell in your body mobilizes to support that. Fear does not exist merely in your mind. It resides also in the tension of your muscles, the clenching of your jaw, and the shallowness of your breathing.

All emotions are the same. Joy, grief, anger, love…they manifest in your movement.

And while you’re probably familiar with the concept of “mind over matter” where your brain can influence the state of your body, the opposite is equally as possible. The set of your body — your posture, if you will — influences the state of your mind.

Just as smiling when you feel down can lift your spirits, so too can standing tall elevate your mood and even improve focus, productivity, and your capacity for solving complex problems.

The Software in Your Muscles

The generally accepted view on muscles is that if they’re tight, you must stretch, roll, and pull them like taffy until they agree to lengthen. Muscles are more or less considered to be a sort of rubber band that has, for some reason or other, become mechanically too short.

Muscles aren’t inanimate objects that spring back into place of their own accord like elastic, though. In fact, a muscle in and of itself has no ability to maintain tone. It requires a signal from your nervous system in order to contract.

Tension isn’t a muscle problem — it’s a software problem. Yes, there are mechanical influences on your tissue. At the site of an injury, the body lays down dense layers of fascia to “bandage” the area. This is what we refer to as scar tissue. It can effectively restrict mobility because the fibers tend not to follow the original grain of the muscle and instead run in every direction, thus fortifying the integrity of the muscle or tendon but restricting mobility.

However, barring any actual scar tissue, muscles become tight because the nervous system tells them to contract. There are many reasons that your nervous system sends these signals, including to perform basic movements like sitting, standing, walking across a room, or reaching for a mug of coffee.

But tension is also a readiness response. Your body tightens muscles to prepare for action, and perpetual readiness, which accompanies chronic stress, results in perennial tension.

Living in Fight or Flight

Everyone is busy. That’s a function of modern, urban life. We all have too many places to be, too many tasks on our to-do lists, and a slew of things that never even get attempted because, priorities.

This kind of modern frenzy results in chronic activation of your sympathetic nervous system — your stress response. This is the branch of your autonomic (meaning, beneath conscious control) nervous system that deals with threat.

The sympathetic branch has a correlate that helps you relax, rest, and replenish your energy: the parasympathetic branch.

In a balanced nervous system, these two have an inverse relationship, meaning they’re not both active at the same time. The sympathetic branches readies you for action while the parasympathetic branch helps you to relax and recover.

Sympathetic:

- Increases heart rate, respiration, and blood pressure

- Mobilizes blood away from digestive function into skeletal muscle to prepare for quick movement

- Constricts blood vessels

- Dilates pupils and focuses eyes

Parasympathetic:

- Reduces muscle tension

- Lowers heart rate and blood pressure

- Aids in digestion

- Slows and deepens respiration

- Supports immune system function

- Aids in the secretion of bodily fluids

Your sympathetic nervous system is like your gas pedal, mobilizing you for action, while your parasympathetic branch is the brake that allows your body to slow down and rest. A healthy nervous system swings, as a pendulum would, between activation and relaxation, never getting stuck to one side or the other.

Sympathetic Lockdown

This pendulum dance is how we maintain what’s called in fancy-schmancy science talk homeostasis. Homeostasis is a balance. Your body is constantly working to preserve it.

But, just like standing on one foot, it’s not a static place. There are millions of tiny micro-adjustments happening in every moment to keep you upright. Balance—or homeostasis—is actually a process of coming into and out of your center, over and over again.

But here’s the thing… when you’re chronically stressed, and thus living in perpetual fight or flight, you don’t get that natural, normal pendulum swing from activation to deactivation. You just stay charged all the time.

And because your body cannot physiologically exist in perpetual activation, it uses your parasympathetic nervous system like a lid to hold down your escalating fight or flight response. It’s a bit like a pressure cooker where the steam is your neural activation and the lid is keeping it in.

When that lid comes off, the whole system blows up.

There are a few side effects of living in chronic activation with your parasympathetic nervous system “covering up” all this stress. One is a type of numbness — officially called dissociation — where you feel sort of disconnected from yourself and lost, or floating.

People who are dissociated often don’t really feel truly alive. Nothing really touches them, and they’ll require ever increasing levels of stimulation to have any sensory experience at all.

In my observation, our whole society is living in this state, which explains why we keep reaching for ever higher levels of extremity — deep, deep tissue massages; extreme sports; bio-hacking; etc.

What I believe we’re reaching for is not higher levels of achievement, but a sensory experience of being alive.

Another common side effect of dual autonomic neural activation is having a hair trigger — sometimes called moodiness or explosiveness. Have you ever met someone who seemed super chill, but randomly flew off the handle at the smallest thing?

That’s a symptom of this kind of dysregulation. You may have heard of really extreme cases, such as the kind of PTSD that soldiers returning from war exhibit, but it exists on micro-levels, too.

Living in a perpetual state of activation—which you probably just call being stressed—is what I term Sympathetic Lockdown. It’s a state where you’re just getting through, moment to moment, without actually discharging the stored tension and neural activation in your body.

Burnout and the Brain

Nobody wants to be stressed, angry, explosive, and emotionally absent from their life. This is not a pleasant place to live.

So, what do we do about it?

We’re just not set up for mental relaxation in our daily lives. There’s constant stimulation from smartphones buzzing and beeping, televisions in every restaurant, and little face to face contact with other humans.

With no built-in triggers for slowing down and dropping into peace, our world is fraught with catalysts for activation, all of it driving us further into burnout.

Burnout is a frightening place to be. Participants in studies on burnout have demonstrated measurable changes to their brains, showing an enlarged amygdala — the fear center1.

In short, burnout doesn’t just make you feel like crap, it also destroys the very structure of your brain.

Most approaches to dealing with stress and fixing burnout focus on controlling either your thoughts or your external circumstances. You either need to think and feel differently about the life you have, or you need to change your reality.

But in a modern world fraught with perpetual triggers, it can be next to impossible to escape the hamster wheel of stress. There’s always one more near-disaster waiting in the wings to give your nervous system a good solid zing.

There is a third strategy that pretty much everyone overlooks: reducing physical stress to calm your mind.

Stress — especially the chronic, perpetual stress that results in burnout — is a form of micro-trauma. In fact, the brains of people diagnosed with burnout mirror those of people who have experienced severe childhood trauma when examined with fMRI1.

The interesting thing about trauma is that it isn’t traumatizing, so long as an organism (person or animal) has sufficient time and resources to release the resulting charge in their nervous system — i.e. to down-regulate the fight or flight response in the sympathetic branch and activate its correlate, the parasympathetic branch.

This is according to the research of Dr. Peter Levine, author and founder of Somatic Experiencing, an embodied trauma healing approach. His research focuses on the ability of wild animals to process trauma. He has found that when the sympathetic charge is released after a traumatic event, there is no lasting effect on the animal.

However, if that activation isn’t fully released, the sympathetic nervous system remains charged and active on some level. Essentially the animal—or the person—remains locked in fight or flight mode.

This is what’s happening to stressed out, burned out people day in and day out.

You’re living on some level as though there were a literal tiger on your heels. And existing in this perpetual state of neural activation results in ceaseless muscle tension, disrupted sleep, an inability to focus, lack of creativity and inspiration, difficulty connecting and relating to others, digestive issues, and even your plain old garden variety generalized anxiety.

Body Over Brain

While mindfulness strategies such as gratitude journals, meditation practices, affirmations, and even psychotherapy are helpful, the reality is that their ability to effect change can only reach so deeply when it comes to your biology.

The aspects of your brain affected by stress and trauma are ancient, primordial. You can’t have a rational conversation with them. Not only do they not speak English (or any other human language for that matter), they also don’t even know that language exists.

But you CAN talk to them — if you learn their language. And when you do this, you have access to the greatest free bio-hack that no virtually one else knows about.

Because just as your mind can influence your body, so too can your body influence your mind. In fact, the body sends signals to the brain far more frequently than the brain does to the body. The heart, for example, contains sensory nerve bundles that send information to the brain about nine times more frequently than the brain sends signals to the heart2.

The body and brain are constantly “checking in” with each other, asking how things are going, ascertaining whether a state change is necessary. Thus, you can think all the happy thoughts you want, but if your body is chronically sending fear and threat signals upward to the brain, it will be nigh impossible to achieve true relaxation.

Balancing Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Activation

While accidents, injuries, and traumatic events usually happened in the past, there is no need to mentally travel back to them. The stored charge in your nervous system is current and happening in present time, so that’s when and where we’ll deal with it.

We’ll use a body-up approach. Rather than trying to talk sense to your nervous system and explain that the tiger in the bushes is simply a figment of its imagination, we’re going to instead learn and make use of its own language: sensation.

Felt sense is a powerful communication tool, but many people have a diminished ability to actually feel their own bodies. Reestablishing this connection can take a little practice, but it’s not hard and anyone can do it with just a modicum of time and attention.

Working with Felt Sense

If I were to ask you what you feel right now, you’d likely tell me that you either feel nothing (or nothing of note) or you would indicate areas of your body that are tight, tense, aching, or painful.

This is true of most people. We either hurt, or we feel nothing at all. But there are tons of sensations happening in your body all the time that have nothing to do with pain. It’s just that you haven’t trained yourself to pay any attention to them.

Developing your sensory awareness is a skill, and the best way to enter into it is through objective description of your present moment sensory experience in your body. For our purposes, you’ll want to describe sensation as though you were a scientist in a lab examining a specimen.

Tight, dense, heavy, warm, dark, gummy, thick, or bubbly are examples of descriptive sensory language. These are helpful. They allow us to get a handle on your body’s experience. What’s not useful are stories about sensation.

Things like…

Sometimes I notice my left shoulder feels a little tight, like when I do an overhead press at the gym.

What usually happens when I’m sleeping is that my arm goes numb and it wakes me up.

My yoga instructor said my pelvis should be more tucked under, like this…

When I’m sitting at my desk, I tend to hunch over and lean on my elbow and I really just need to strengthen my back muscles more, I think.

These are an intellectualized version of your experience. They come from floating above your physical sensations and analyzing them in a detached, clinical way. What we want is for you to connect to the sensory experience directly. In this way, you’re able to converse with your biology.

The Felt Sense of Feeling Good — Resourcing

We’re conditioned to seek and destroy problems, but when it comes to stress, trauma, and burnout, this problem-fixated focus is actually causing you a lot more pain. If the underlying tension and tightness that are causing your discomfort are related to sympathetic lockdown—and they are, I guarantee it—then focusing on the pain perpetuates the threat response, and thus the tension.

One way we can back ourselves into pain relief is by using a little reverse somatic psychology and putting your attention on the areas of your body that feel really good. In this way, we’re creating a sense of safety for your biology which effectively allows it to discharge the stored sympathetic nervous system activation.

This is a form of resourcing — using people, places, things, experiences, and even sensations that have a positive impact on your well-being to create a sense of safety and connection that soothes your nervous system.

This is a relatively easy practice that can be done anywhere, but until you develop your skills a little bit, it’s best to be in a private, quiet location where you won’t be disrupted.

- Sitting, standing, or lying down, scan your body with your attention. What sensations feel pleasant?

- Because it can be difficult to notice your sensory experience in a vacuum at first, I like to employ one of Dr. Peter Levine’s practices to jumpstart your awareness:

- Place your right hand under your left armpit, flat against the rib cage. Place your left hand on your right shoulder. You should now feel as though you’re giving yourself a hug. Notice what feels pleasant about this position.

- Use sensory language to explore the feeling. Describe the pressure, temperature, and weight of the sensation if you can. Remember to use words like warm, tingling, sticky, dense, thick, light, empty, firm, etc. and not to delve into mind chatter or stories about why you feel the sensations that you do. Stay in your body.

- Focus your attention on positive sensations—things that feel pleasant, safe, and secure. When you have a firm grasp of a positive sensation, see if you can expand the feeling just a little bit further into your body. For example, if you have a warmth surrounding your heart that’s comfortable and cozy, see if you can spread that glow a bit, maybe extending it out to your shoulders, up to the base of your throat, or downward into your abdomen.

Spend at least a minute, but longer if you like, exploring this pleasant sensation expanding in your body. Once you feel complete, release your arms and notice how your body feels overall.

What has shifted? Is there less tension in your shoulders and neck? Have painful symptoms dissipated? Do you feel calmer and more centered?

Focusing your attention on pleasant sensations in your body is something you can do at any time of the day, no matter where you are, to down-regulate stress responses and restore neural balance.

You’ll notice the tension in your muscles dissipate, your breathing will slow. Often, colors become brighter as your vision clears and mental focus improves. These are all effects of discharging sympathetic lockdown.

Resourcing as a Skill

Resourcing and working with felt sense are tools that take some time and practice to develop, but they have a profound impact not only on your physical and mental well-being, but also on focus, productivity, and performance.

Of course, as with anything, developing skill in this practice takes time and effort. Somatic Experiencing practitioners can help you to finesse your technique, but you can also work on your own.

There’s an entire chapter in my ebook dealing with neural regulation, including detailed information on working with felt sense and specific practices to help you calm your stress response. You can order it here.

1. https://www. psychologicalscience.org/observer/burnout-and-the-brain

2. Blake, Mandy. “1.2 Heart Brain” Body=Brain.

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.