Tight neck muscles and a lack of neck flexibility are common complaints. Many people find that their neck gets stiff after hours spent peering at spreadsheets on a laptop, traveling in airplanes, or even just sleeping.

If you wake up with a stiff neck, find it difficult to look over your shoulder without twisting your entire body, or if you suffer from frequent tension headaches, you may want to address your tight neck muscles.

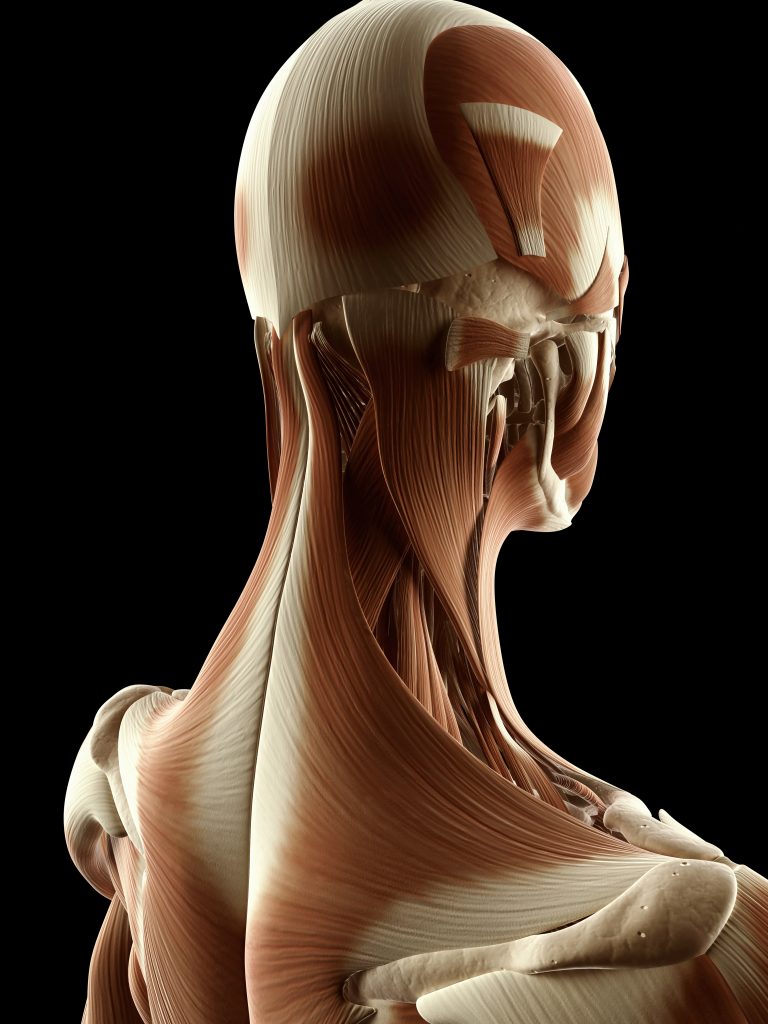

Of course, before we dive into the nuts and bolts of loosening your neck and shoulder muscles, let’s take a quick look at anatomy. I find it incredibly helpful to be able to picture what I’m working with when I’m stretching my own body, and many of my clients report that it’s useful for them as well.

Anatomy of Your Neck

Your neck as anatomically described is comprised of seven vertebra that link your skull to your thoracic spine, or middle back. Of course, these vertebra don’t just hang out on their own, completely isolated from the rest of your spine.

When you turn your head, your neck twists, sure. But that movement should travel down into your thoracic spine, too. If your mid-back is stuck and rigid, your neck will experience limited range of motion and impaired flexibility.

The muscles of your neck largely connect the vertebra upward to your cranium and downward to your ribs and shoulder girdle. It’s not necessary to memorize these muscles, but it’s useful to understand that they don’t exist solely within the structure of your neck but rather as links to the rest of your body.

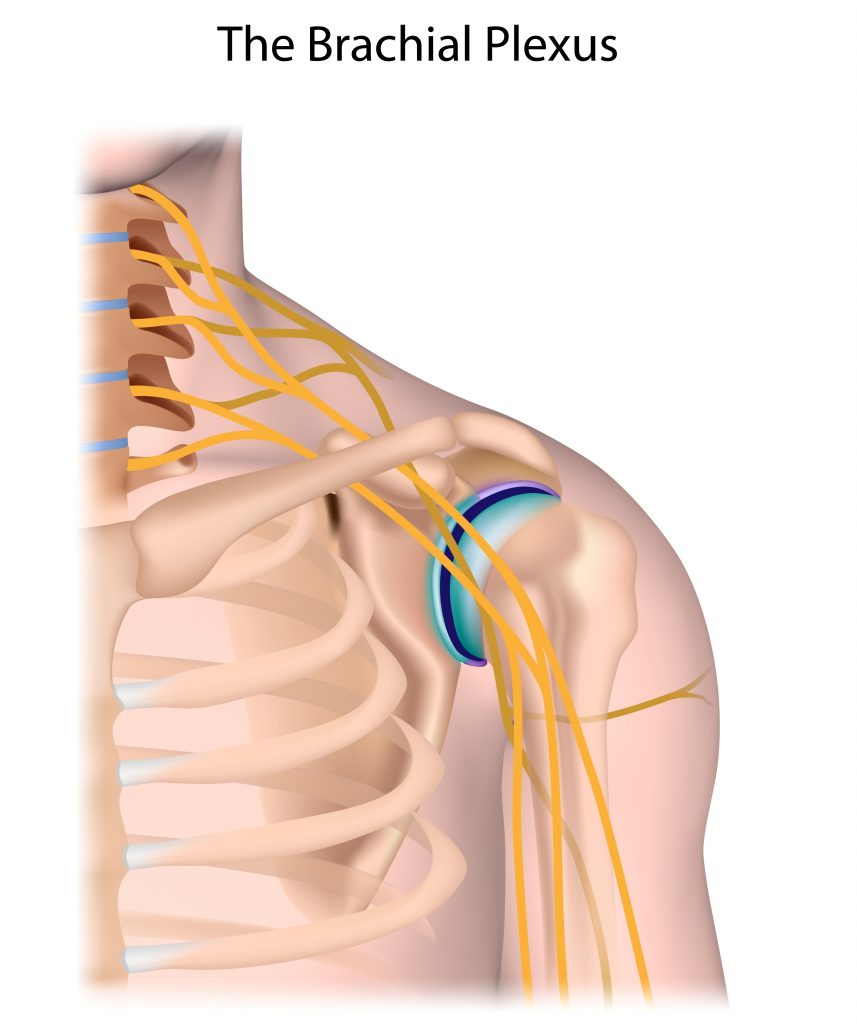

Stiffness in your neck is related to shoulder and back tension as well. Often, radiating pain in your the arms and hands can be traced to restriction in and around your neck and shoulders that clamps down on a nerve, limiting its ability to glide and irritating the fibers.

One such place that this happens is within the brachial plexus, a large nerve bundle that exits the spine in your neck, crosses over your first rib and extends into your armpit area. Any tension or restriction in your neck or shoulder muscles can cause impingement to these nerves. Sometimes lying on your side can exacerbate tightness, resulting in numbness or tingling in your hands or arms.

The Connection Between Stress and Neck Tension

Ask anyone where they store their stress and I’d put money down that nine out of ten times, the answer will be in the shoulders. It’s a universal truth that stress makes our backs and shoulders clench in defense.

As you can see from our discussion of neck anatomy, tight shoulder muscles are also tight neck muscles. They’re really not separate. They’re not even different muscles. Neck muscles are shoulder muscles. Shoulder muscles are neck muscles. It’s the same structure.

(Which begs the question, really: what exactly is a neck? Where does it truly start and where does it end? All division within the body is artificial and contrived, an artifact of an anatomist’s scalpel.)

There are other effects of stress which contribute to tight neck muscles as well. Stress and trauma results in a biological flexion response from the nervous system designed to protect your vulnerable organs and genitals. In short, it’s an innate response for humans to curl into the fetal position, even mildly, when placed in a stressful situation.

Years ago, someone sent me a fantastic study that looked at photographs of people under varying degrees of stress, including images of political prisoners who had been undergoing interrogation. It’s been probably a decade and I can’t find the dang images, but I wish, wish, wish I’d saved them.

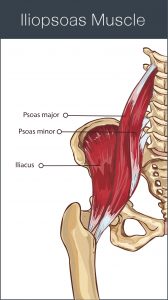

It was fascinating to look at how in every scenario, even if the person was standing upright, there was contraction through the core, shortening the psoas — a deep core muscle stretching from the base of the diaphragm across the front of the hip and inserting on the upper thigh bone.

Stress, Stretching, and Flexibility

There is a physical tug on a neck that exists in a stressed out body with a tight core. Shortening in the psoas and associated tissue (remember: one muscle never tightens in isolation but only as part of a larger complex) constricts the spine, inhibits the function of the diaphragm — your primary breathing muscle — and draws the chest downward.

When your sternum — or breastbone — sinks in and down, your entire rib cage then effectively hangs like a giant anchor slung from the delicate muscles and vertebra of your neck. These structures aren’t designed for such heavy lifting. No, in fact, your neck is intended for movement. It is, in effect, your antenna, the branch of your body that moves the sensory organs of your face around, taking in information from the world around you — seeking food, watching for threats, connecting to other humans, relating.

And so, when your neck is put upon to do the job of holding up your rib cage, the result is tight muscles and a lack of mobility.

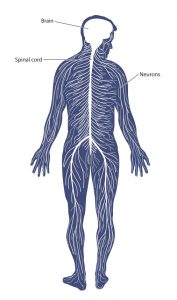

Of course, in addition to this physical burden on your neck, stress creates a physiological effect as well. Stress in any form — even in its beneficial state — activates the sympathetic branch of your nervous system. You may be more familiar with this as your fight or flight response.

This is a good thing. You need sympathetic neural activation. Without it, you’d never do anything. It’s your motivation. It drives you to eat, connect, to stay alive.

But chronic activation without discharge is very damaging, indeed. Long term, low-grade stress has this exact effect on your nervous system.

Not only does the physical flexion of your core and psoas muscle impinge your diaphragm, creating a shallow breathing pattern that perpetuates stress activation in your body, the ongoing stress causes a body-wide threat response, elevating cortisol, accelerating your heart rate, raising blood pressure, and triggering muscle tension.

Therefore, while moving the muscles (i.e. stretching) is helpful to dissolve tension, the state that your body is in also plays a significant role. Calming this stress response not only decreases muscle tension in and of itself, it also makes your body more receptive to stretching and movement practices.

How to Calm Your Stress Response

There are a million ways to reduce stress. Most of them deal with the mind — controlling your thoughts, focusing on gratitude, avoiding negative thinking loops, meditating, etc.

These are excellent practices and can be useful for handling stressful moments. But the ultimate metric of a stress management technique is: does it calm your sympathetic nervous system activation and stimulate the opposing response in your parasympathetic (rest, relax, restore) branch?

Many of these practices do, in fact, have that effect. However, these are all brain-based, meaning you have to work to control something that’s a bit ethereal and hard to get your hands on: thoughts.

We’re such a mind-focused society, believing that all our power lies between our ears. And yeah, the brain is pretty cool and can definitely have an effect on the body. But your body can — and does — also affect the brain.

Therefore, a more tangible strategy to discharge stored stress can be to focus on decreasing muscle tension. One symptom of stress that greatly contributes to tight neck muscles is a clenched jaw. Many of my clients who experience neck pain and stiffness also report teeth grinding and TMJ issues.

First Relax Your Jaw

The first thing I recommend when dealing with neck tension is to focus on softening your jaw muscles. You can do this right now, wherever you are. It takes no special skills or equipment.

Simply bring your attention to the tension in your chin and jaw area. Inhale deeply and slowly, and then as you exhale, soften the muscles holding your jaw in place. It won’t fall off, I promise.

Relax your lips, soften your eyes. Allow your vision to blur slightly, to grow diffuse. Release tension from the muscles around your eyes and cheeks.

Let your jaw drop and mouth open slightly. Imagine your entire mandible sinking lower, opening from the back first (your jaw doesn’t, in fact, open like a hinge, but rather glides downward in the back to lower the entire bone).

Gently wiggle your jaw back and forth, right and left. Jut your chin a bit forward and back, sliding your jaw in and out. Move slowwwwwly! The more slowly you move, the more opportunity you give your nervous system to feel the sensory stimulus being generated, which calms your body.

Focus your attention on your ears. Can you relax the muscles around them? It’s totally okay if you can’t wiggle your earlobes or anything, just think about softening the tissue that’s around them. If it helps, place your fingers on the areas just in front and just behind your ears to help you feel them better.

Notice your breathing. Do you feel it deepen and slow as you release tension in your jaw, cheeks, eyes and ears?

Stay with this practice for as long as you feel progress happening. If you have quite a lot of stored stress and/or you’ve been stressed for a very long time, you may find that it takes ten minutes or more to feel a full relaxation response. In some cases, it make take half an hour, forty minutes, or even longer.

You don’t have to spend that much time, of course, but be cognizant of the fact that your biology isn’t on any schedule. It’s operating on primordial time, where it has the space of millennia to change.

Then Release Tight Neck Muscles

Only after you’ve completed the above should you move on to the video practice below. This video will walk you through some movements to restore flexibility to the muscles in your neck while also lubricating the small joints between your vertebra.

You will get far more out of this practice if you enter into it in a relaxed state, first making use of the techniques above. Relaxation calms the nervous system, making your muscles more receptive to stretching and mobilization techniques.

Otherwise, you’re merely stuck in a tug of war with your own nervous system, and that’s just exhausting.

For more great tips on how to calm your nervous system in order to decrease tension and increase flexibility, check out my ebook Perfect Posture for Life. It encompasses my more than thirteen years of experience helping hundreds of clients to improve posture and movement. You can order it by clicking here and start alleviating the pain caused by tight muscles immediately.

The gray matter of your brain condenses down to a ropy cord of neural material that runs through the core of your spine, branching out along the way into millions of nerves that terminate in muscles, bones, and organs.

The gray matter of your brain condenses down to a ropy cord of neural material that runs through the core of your spine, branching out along the way into millions of nerves that terminate in muscles, bones, and organs.

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.