Is upper back, neck and shoulder pain the bane of your existence? You’re definitely not alone.

Over half of all Americans experience back pain symptoms every year1, yet the medical establishment’s ability to address spinal pain is fairly limited. Doctors rely on anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxers to alleviate the symptoms, turning to spinal surgery for more acute cases.

While I’ve seen surgery help some of my clients in more dire circumstances, it’s a bit terrifying that spinal surgery fails to resolve a patient’s condition so frequently that there is actually an official diagnosis for this lack of result: failed back surgery syndrome.

Perhaps even more frighteningly, doctors have been recently found to be splitting their attention across multiple operating rooms at the same time2 and taking kickbacks from medical device companies3. It doesn’t take a leap to realize that a person struggling with chronic back pain is facing a dire situation fraught with risky and possibly perilous choices.

Yikes. With all of our advanced imaging and research, why are doctors still unable to address such a common health complaint?

Understanding the Spine

From my perspective, the reason that people aren’t getting the help they need for stiff, aching backs is that the way Western medicine views the spine is somewhat limited.

That view is reflected linguistically in our reference to the backbone as a spinal “column.” When we talk of firmness in the context of having good boundaries, we refer to “having a spine.” In short, the cultural view of the spine is as something rigid and unyielding.

And surgeries mirror this concept. When a doctor recommends spinal surgery, what they’re likely going to do is increase stability and decrease movement by fusing vertebrae. However, according to Dr. Charles Rosen, clinical professor of orthopedic surgery at the University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine, “Maybe 5 percent of patients with back pain need surgery.” Yet in the United States alone, over a million people undergo spinal surgery each year3.

That means that a vast number of people who experience debilitating spinal problems undergo unnecessary surgery every year that reduces range of motion and flexibility of the spine while not resolving their symptoms.

Your Spine is A Slinky, Not a Strut

There are many reasons why surgeries fail. The doctor did a poor job, or the problem wasn’t accurately diagnosed in the first place. But in my view, a major component of the failure of spinal surgery is that your spine isn’t meant to be a rigid structure.

Structure of the human spine, side view.

While absorbing compressive force is one function of the spine, in a living body that bony column also has to facilitate movement. I envision the spine functioning more like a spring, or a slinky. If you look at the anatomy of your spine, you’ll see that viewed from the side, it has three curves, one each at your neck, mid back, and lower back. You could also count the fused sacrum—the bottommost bone of your spine—as a fourth curve.

These curves function to absorb load and shock as you sit, stand, walk, and run through life. Each time your foot strikes the ground, a shockwave goes through your body. There are many structures designed to help your body cope with and dissipate this shock, but your spine is definitely a major one.

The cartilaginous discs between your vertebrae absorb shock, provide ligamentous support and allow for a measure of independent movement between the bones.

If your spine were meant to be a column—a rigid, supportive structure that connected your head to your pelvis and had no other function than to hold your head upright—it would be straight.

But it’s not like that at all. In addition to the curves that help your spine to spring, it’s comprised of twenty-four individual vertebrae (not counting the fused ones in your sacrum), separated by cartilaginous discs that also aid in absorbing compressive shock while allowing for independent movement.

The Spine Generates Movement

Your spine essentially serves three purposes. The first is to protect your spinal cord, the thick rope of neural material that runs through its center. Second, your spine provides flexible support for load bearing and movement. And third, your spine has to allow mobility in your torso—to bend, flex, and rotate.

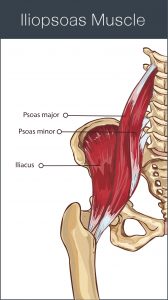

Muscles of the deep abdomen and upper leg related to core locomotion.

Professor Serge Gracovetsky, author of The Spinal Engine, studied the spine extensively and found that in addition to the above functions, the spine is a primary generator of locomotion. What that means is that the human gait, previously believed to be primarily a function of the legs, actually stems from the spine4.

So, you’re not a stiff torso carried around by a pair of sticks (legs). Movement stems from your core, initiated by a lateral bend to your lumbar spine.

This makes quite a lot of logical sense when you examine the connection of the psoas, a deep abdominal muscle that originates at the front of the spine, to the upper thigh.

Hope for Back Pain – Prioritizing Resilience

In virtually every case of back pain—upper back pain, lower back pain, middle back pain, back pain on one side, back pain that spans both sides—my clients’ symptoms have shown improvement when the spine became more mobile, not less.

In fact, when assessing a person’s movement, I watch them walk and look for places that don’t allow movement to translate through the spine. It’s a bit like looking for rocks blocking the flow of a stream.

A mobile spine is a resilient spine, while a stiff, inflexible one is prone to injury. My experience with my clients has shown me time and again that restoring mobility to areas of the spine that have become stiff, fixed, or rigid releases tension from surrounding musculature and alleviates pain.

And this is yet another reason that the traditionally accepted definition of posture as a rigid pose, placing your body into straight alignment and holding it there, is less than ideal. The kind of inflexibility generated by such a practice makes you brittle over time and reduces the number of options your body has for movement.

Fixing a Hunched Back

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.

The mid back is an area prone to tension, especially in those who spend hours sitting or standing at computers day in and day out, resulting in a depressed sternum.

When the rib cage collapses downward, it causes your belly to pooch forward and your upper chest to flatten. The result is a kyphosis in your thoracic spine—increased curvature of the mid back, like the beginning of a hunchback.

This posture provides no support for your head. Your neck is forced into a forward angle and the result is head-forward posture.

Neck and Upper Back Pain Stretch

This practice will elongate the thoracic spine, restoring mobility and decreasing tension.

1. Stand arm’s length away from the wall. Put your palms flat against the wall and spread your fingers wide.

2. Keeping your palms against the wall, step back and stretch out so your hands are directly overhead and you’re looking down at your toes with your ears squarely between your arms (Fig.26). Pull your belly button gently toward your spine to protect your low back.

3. Press your palms into the wall with a slight downward pressure, like you’re trying to slide the heels of your hands down the wall. Engage all the muscles of your arms and shoulders, using 100% of your strength to press into the wall. Remember to keep your belly button engaged.

4. Hold this isometric contraction for 15-20 seconds and then relax, deepening the stretch. Be careful not to let go of your belly button and let your low back hyperextend when you relax. You should be able to press your chest forward and down further.

5. Repeat this 2-3 times, deepening the stretch a little more with each repetition.

Mid Back Exercise for Upper Back Pain

In this practice, you’ll be waking up the muscles of your back and shoulders to “turn them on” so that your body can use them as you move about your life.

You’ll need a wooden dowel or short stick of about eighteen inches in length.

1. Lie on the floor or on a yoga mat, face down.

2. Place your arms out in front of you, palms up. Grasp the stick or dowel in your palms with your hands shoulder-width apart and your elbows bent.

3. Keeping your elbows in line with your wrist and your head in line with the rest of your spine (don’t lift your chin and look up), lift your elbows a few inches off the floor and hold for a count of ten.

4. Repeat for six sets, holding for ten seconds each time. If this is too long, drop down to only five seconds for each set. Don’t over-exert! There is no benefit to doing more than your body can handle.

You can find more posture-correcting practices just like these in my ebook, Perfect Posture for Life. Learn more and order the book by clicking here.

1. https://www.acatoday.org/Patients/Health- Wellness-Information/Back-Pain-Facts-and-Statistics

2. Baker, Mike, and Justin Mayo. “Swedish double-booked its surgeries, and the patients didn’t know. The Seattle Times, 28 May 2017. Web.

3. http://www.orthopaedicsurgery.uci.edu/pdf/rosengoodhousekeeping.pdf

4. http://www.alexandertechnique-running.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/The-Spinal-Engine.pdf

Leave a Reply